In this case, they took Pitt’s face, fast-forwarded it five decades, and then stuck it on the torso of a diminutive actor. CGI geeks take this raw data and manipulate it as they see fit. The glowing footage from each camera is then melded into a single composite image, thousands of times more detailed than conventional motion-capture methods.ĥ. It looks as if the lights are continuously on in the studio. This process happens so quickly (90-120 times per second) that human vision can’t perceive it.

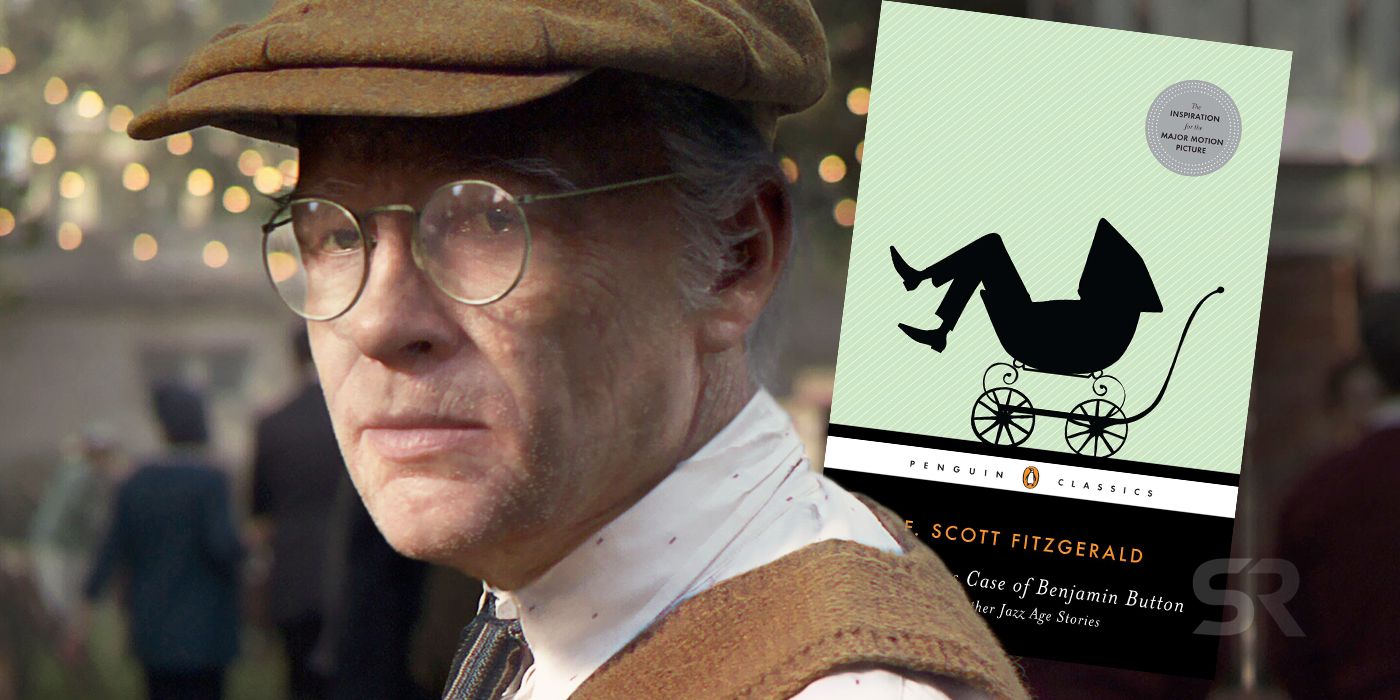

When the lights blink off, the grayscale cameras wink on and record the phosphorescent detail of anything that’s coated with makeup. When the fluorescent lights are on, the shutters of the color cameras snap open. Perlman is the founder of special effects company Reardon and inventor of a technique that would make Pitt’s metamorphosis from cantankerous geezer-child to octogenarian toddler more convincing than Tina Fey’s Sarah Palin impression. So Fincher turned to Steve Perlman for help. Problem is, current-gen performance-capture techniques - sticking a bunch of dots onto the actor’s face, recording their movement, then applying the data to a 3-D model - miss subtle nuances the resulting virtual visages often look stiff and creepy (see: The Polar Express). CG was the answer: Make a 3-D model of Pitt’s visage, fast-forward it five decades, and stick it on the torso of a diminutive actor. For David Fincher’s film adaptation, out on Christmas Day, the director had to find a way for Button (Brad Pitt) to "reverse-age" convincingly.

Scott Fitzgerald’s 1922 short story The Curious Case of Benjamin Button has a bizarre premise: The protagonist was born looking like an octogenarian, then appeared younger and younger as he got older and older.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)